What do Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) stand for?

Non-fungible tokens are growing rapidly and now have many uses. While digital assets now benefit from a clearer legal framework since the PACTE law, legal analysis of the NFTs reveals that they remain outside the framework.

ICOs have made it possible to popularise the notion of token, understood as a digital token operating on a blockchain and allowing the use of an application or the representation of a right. For example, the BAT (Brave Attention Token) token – which runs on the Ethereum blockchain – serves as a means of payment within the Brave browser. Consequently, this type of token is fungible: each unit is identical in nature and value.

In search of a “unique and rare” token, Dieter Shirley invented an NFT standard (ERC-721) in September 2017, thus democratising this new type of non-fungible blockchain token. Like a cryptocurrency, it can be used on applications supporting the aforementioned tokens, and can be stored in a wallet.

To date, the most popular use of NFTs is in games such as CryptoKitties – the successor to Pokémon cards or the famous Panini stickers – where players collect characters based on their rarity. In this blockbuster framework, rarity is materialised by NFTs, acquired or exchanged between players or from the publisher.

What is the difference between a Panini card and NFTs representing a CryptoKitty ?

What legal regime for NFTs ? Are they digital assets (in the sense of the PACTE law) like the others ?

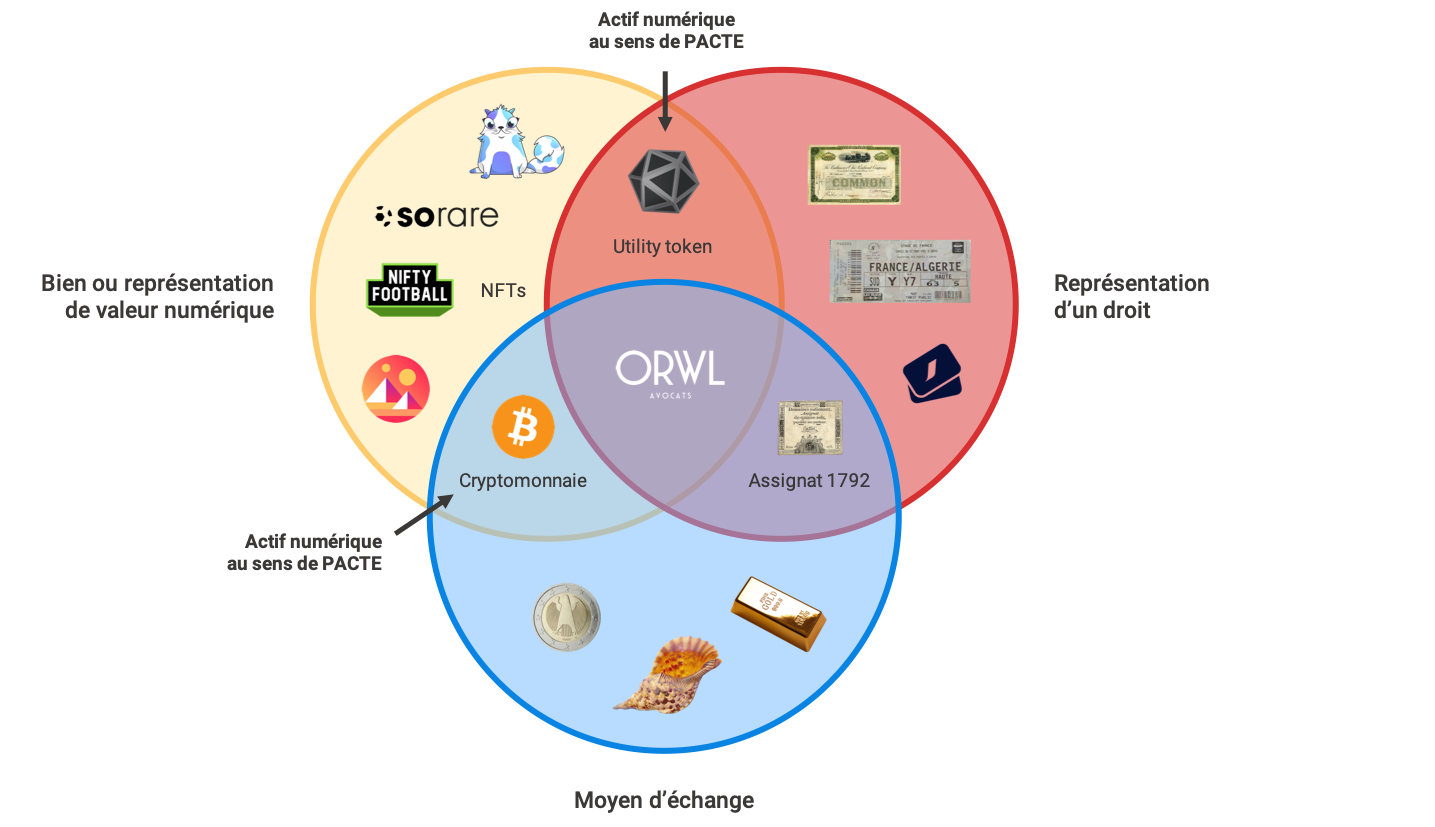

In accordance with the principle of technological neutrality – substance takes precedence over form or medium – the NFT will be regulated according to the nature of the rights or object it represents: a title, a right, a work of art, etc. As such, the sale of NFTs that “promotes a financial return” could be prohibited on the basis of the general property intermediation regime.In light of the new legal definition of digital assets and the legal analysis of NFTs, NFTs cannot be considered as such, thus escaping the regulations applicable to the issuance of tokens and the provision of services on digital assets. Indeed, :

- On the one hand, an NFT cannot be qualified as a digital token insofar as it is the object of the property right held by the user and not the representation of “one or more rights” within the meaning of the legal definition.

- On the other hand, the NFT also falls outside the definition of cryptography. Although it can be “transferred, stored or exchanged electronically”, it does not constitute a means of exchange. This observation seems logical to us with regard to the objective of controlling excesses and limiting the risks posed by the emerging “crypto-finance” sector, to which the NFTs, with their playful or artistic vocation, do not belong.

Consequently, the anti-money laundering rules are not applicable to the sale of NFTs, nor is there a ceiling on payments in cash (€1,000) or electronic money (€3,000) when they are acquired in cryptos.

Finally, the NFTs also raise tax issues in light of the new regime applicable to gains on digital assets, which devotes a 30% flat tax. If one follows the legal analysis of the NFTs that precedes and leads to their exclusion from the category of digital assets, the gains they are likely to generate remain under the previous law, namely :

- the regime of capital gains on movable assets for occasional activities (rate of 36.2%) with the exemption of sales of less than €5,000, accompanied by the deduction for the duration of ownership ;

- the application of the income tax scale for usual activities, likely to concern hypothetical “NFT traders”.

The combination of these provisions leads, de facto, to the non-taxation of gains from the sale of NFTs, except for exceptional amounts such as the CryptoKitty sold for $140,000.